Methodology deep dive 🤓

Hello from SurveyMonkey! In this week’s newsletter, we’re taking you behind the scenes to share some of the methodological considerations we think about when we’re writing a questionnaire. First, we’ll share some new research findings we learned while attending a conference for public opinion researchers last week. Then, we’ll walk through the results of a quick survey experiment we fielded recently.

Three💡 research topics we were tracking at AAPOR

How to ask about gender. Demographic questions–especially gender–are often sensitive topics for respondents, and understanding how to ask them in a way respondents can understand and appreciate is important. Read more from SurveyMonkey on SOGI questions here.

Survey data quality. What’s the best way to judge whether a survey is high quality? The usual tools researchers use include looking for speeders (people who complete a survey too quickly), straightliners (people who give the same answer to several questions in a row), and respondents who fail various “trap question” tests embedded in a survey. Check out SurveyMonkey’s recommendations for data quality here.

Probability vs. non-probability surveys. Most people using SurveyMonkey will be based on a non-probability sampling methodology. As non-probability surveys become ever more prevalent, methodologists (including our Research team!) are continuously exploring new ways to calibrate the results from non-probability and probability samples. Learn more about nonprobability sampling here.

Why question wording matters

In the spirit of sharing survey best practices, we’re dedicating this week’s newsletter to the importance of question wording. As The Pew Research Center notes, the choice of words and phrases when writing surveys is critical: “even small wording differences can substantially affect the answers people provide.” Proper question wording should allow the respondent to answer with reliability, i.e. if asked the same question again, they should give the same response.

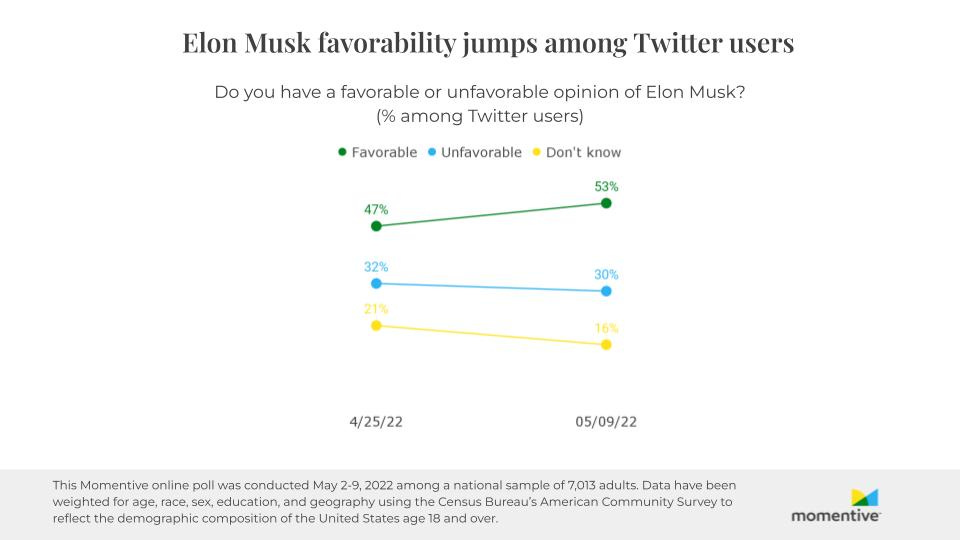

In a recent SurveyMonkey poll, we ran an experiment to test just how much question wording matters. If you read our newsletter last week, you’ll recall that we asked respondents to rate the favorability of four tech billionaires: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, and Bill Gates. We found that Musk’s favorability had increased over the prior two weeks, while he has been in the news regularly for his (possible) takeover of Twitter.

In the experiment, a randomly selected half of the respondents were asked the series of favorability questions with each person’s title (i.e. “Do you have a favorable or unfavorable opinion of Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla and SpaceX”), while the other half of respondents were asked the same favorability questions without the detail of who each person is.

In almost every case, respondents were more likely to say they “don’t have enough information to say” how they would rate someone when the person’s title was not included.

For Bezos, changes in unfamiliarity were particularly noticeable without his title: 26% didn’t have enough info to say with his title included in the question, yet without his title, this percentage jumps to 35%.

Bezos’s favorability rating decreased too: without his title, Bezos had a favorability rating of -20 (21% favorable, 41% unfavorable, 35% don’t know). With his title, Bezos’s favorability rating decreased 4 points to -24 (29% favorable, 43% unfavorable, 26% don’t know).

Similarly, without including Zuckerberg’s title in the question, adults were less familiar with the Facebook founder: 27% of adults didn’t know enough to say compared with 21% when Zuckerberg’s title was included. Respondents were also slightly more likely to have an unfavorable opinion when his title was included than without his title (59% vs. 54%).

Differences weren’t quite as pronounced for Musk: with his title included in the question, 23% didn’t have enough info to say whether they favor him or not, but without his title, this percentage increases slightly to 26%.

Gates was the only exception: there was no real change in the percentage of those who don’t know him with his title included in the question, 23% didn’t know enough to say; without his title, 24% didn’t know enough to say. So, in comparison to Musk, Bezos, and Zuckerberg, the majority of adults are familiar enough with Bill Gates to have an opinion, with or without his title. Interestingly, with Gates’s title included, adults were slightly more likely to view him as favorable than without his title (39% vs. 35%).

That’s all for this week! Thanks as always for reading.